Who is excluded from being a “first-gen student”?

The University of Minnesota says a student is first generation if neither parent has a four-year degree, but some want the definition expanded.

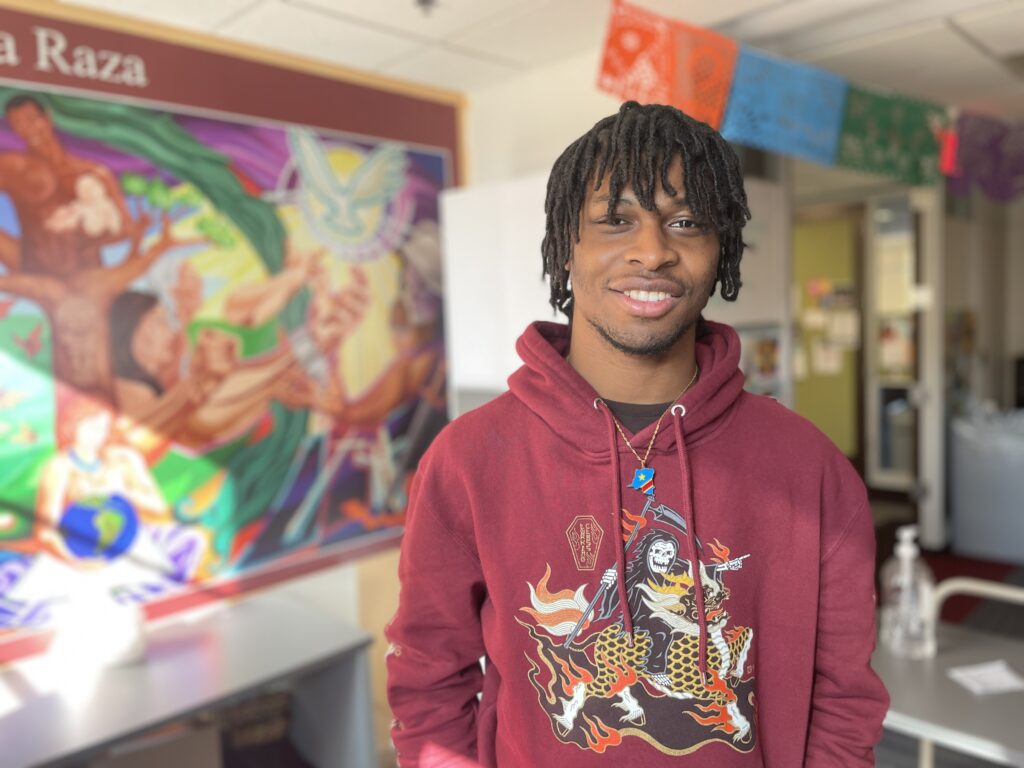

Fourth-year undergraduate Cedric Banzeba in the Mi Gente Student Cultural Center on Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. Banzeba identifies as a first-generation college student and is a member of the Latinx student group.

By Jessy Rehmann

Cedric Banzeba thought college would be like high school. He didn’t know how to register for university classes, was unaware he had an academic adviser and didn’t understand financial aid.

“It was kind of hard to dive into college,” said Banzeba, who transferred to the University of Minnesota after two years at St. Cloud State University. “I didn’t know what to do or how to navigate anything. It was basically me on my own.”

Banzeba, 22, is now a fourth-year student who expects to graduate in 2025. He said his immigrant parents could not teach him the complexities of higher education. Because of this, Banzeba identifies as a first-generation college student.

Recently, he wondered if the University of Minnesota’s definition of “first-generation student” includes him. His parents have degrees, although most are from universities outside the U.S.

The university considers an individual a first-gen student if neither parent has a four-year degree. This definition is derived from an amendment to the federal Higher Education Act of 1965.

Many colleges use these guidelines for categorizing first-gen students, but some explicitly broaden their scope to include students whose parents earned bachelor’s degrees from foreign countries. The University of Minnesota has not done this.

“I understand that my parents did go to college, they went to further their education, but this is my education as a firstborn student in the U.S.,” Banzeba said. “I have to navigate myself here. My parents weren’t born here, so they can’t really help me as much.”

Expanding the first-generation definition

Terra Brister, the interim assistant director of holistic student support at the university’s Multicultural Center for Academic Excellence, said the university needs to expand its official definition of “first-generation student” to include any student who does not have a prior understanding of the processes, resources and cultural contexts of higher education.

Considering these students as first-gen would give them clearer access to advisers who specialize in guiding students through the intricacies of college, Brister said. This is why the multicultural center, also known as MCAE, opens its first-gen initiatives to any student who needs additional support.

“I would like to debunk that assumption that just because your parents went to college, you magically know all the answers,” said Brister, who was the first in her family to obtain a bachelor’s degree. “Like if your parents went to college out of the country, that is vastly different than the U.S.”

While MCAE staff are discussing how to make the label “first-gen student” more inclusive, the university currently does not have a plan to change the official definition, according to a written statement from Jake Ricker, the university’s senior director of public relations.

“I have no doubt those ongoing discussions will continue,” Ricker wrote. “And we’ll see where those lead.”

Despite parents’ degrees, student needs support

Banzeba’s situation is an example of how the current first-generation student definition can be confusing and falls short. His mother has a college degree from her home country of Cameroon. His father, who is from the Congo, has two bachelor’s degrees: one from a university in Switzerland and one from the Minneapolis campus of St. Mary’s University.

Banzeba’s father obtained his U.S. degree when Banzeba was in seventh grade. That circumstance might reduce the impact of the degree on college-bound children.

According to a 2023 report by The Common Application, parents who earn bachelor’s degrees after the birth of their children may not be able to pass on the same level of guidance or financial stability as families with longer histories in higher education.

For his U.S. degree, Banzeba’s father paid completely out-of-pocket. When Banzeba was in high school, his parents said they expected him to finance his own education as well.

Banzeba learned how to get loans, complete the Federal Application for Federal Student Aid and apply for scholarships all by himself. Banzeba is now over $75,000 in debt and said he is worried about starting payments in December.

“I’m kinda paying this on my own, without any financial help from my parents,” Banzeba said. “So that’s why it’s a little tough for me to grasp how I’m going to manage my finances and stuff. I was just told, ‘You need to save money.’”

How the “first-gen” identity connects students to resources

If the university recognized more people as first-generation students, Brister said students like Banzeba would feel more clearly validated in their struggles and would be more comfortable asking the institution for academic and financial guidance.

Being considered a first-generation student encouraged MCAE First-Gen Intern Dola Greene to connect with resources that answered her many questions about college, she said. A current fourth-year undergraduate whose parents have two-year degrees from Nigeria, Greene did not know she fit into the category until she received college acceptance letters that identified her as first-gen.

Through her work at MCAE, Greene said she has noticed many first-gen students do not know what university resources are available, much less how to access them.

“I think that’s the big issue with first-gen students,” Greene said. “It’s like they don’t even know what there is to know.”

To empower more students to utilize first-gen resources, Greene and Brister made multiple posts on the UMNFirstGen Instagram account highlighting the many ways to define first-gen college students.

The posts challenged people to broaden their understanding of the label. They noted “first-generation student” can include those whose parents earned degrees outside the U.S., those whose parents were the first in the family to receive degrees and “any student who may self-identify as not having prior exposure to or knowledge of navigating higher institutions.”

“Because there are all these various definitions, I think a lot of people had the assumption that maybe it was just a four-year degree, or maybe, I have to look a certain way, or my background had to look this way,” Greene said. “I think just expanding the definitions maybe allowed more people to be like, ‘OK, I resonate with this, so let me seek help through that.’”