It spotlights Black individuality at the University of Minnesota, but can it move from words to action?

By Jarrett George-Ballard

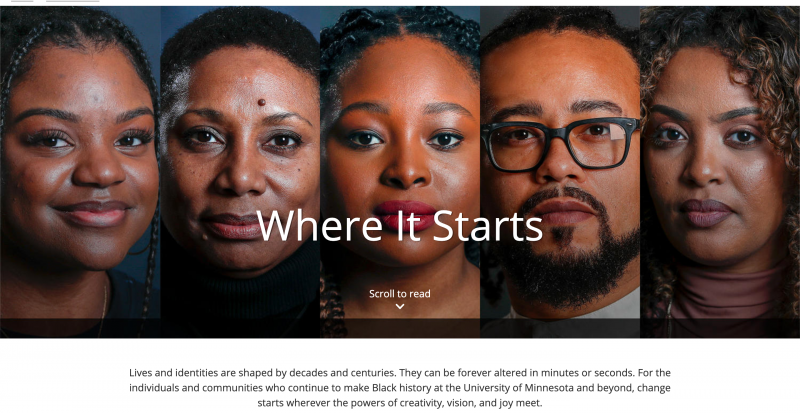

When the University of Minnesota launched “Where It Starts” to celebrate Black History Month, Black students and faculty noticed it took a different approach from the University’s usual promotion of Black-centered activities and the Campus Climate initiative.

The new initiative’s collection of personal stories through videos, interviews and articles sought to highlight Black students’ experiences and their excellence, with each story reflecting on overcoming obstacles, building community and finding purpose, according to Shari White, a digital strategist with University Relations and one of the project’s creators.

“All of the stories featured in the ‘Where It Starts’ series exemplify that change starts wherever the powers of creativity, vision, and joy meet,” White said in an email. “Each story concludes with advice on how our readers can take meaningful action while they continue their journey at the U of M Twin Cities.”

Manyi Ayuk, a fourth-year student studying psychology and public health, is featured in the series discussing her experience as a Cameroonian American and the challenges of that dual identity. She said she loves her Blackness because there’s a lot of power, joy and culture associated with it.

“I think that the U’s decision to make this series shows an actual commitment to representation, diversity and inclusion because obviously authentic stories from people in our community carry more weight than any banner a digital designer could slap on the MyU landing page,” Ayuk said.

As to why the University is doing this now? “My answer is, we need this done yesterday,” Ayuk said. “But I think it was a particularly good choice to give actual Black community members at this University authorship of our stories in the aftermath of George Floyd in Minneapolis.”

While the series wins praise for elevating and centering Black students’ voices and experiences, it raises strong questions for some Black students and faculty.

“Truthfully, I feel like the U should’ve done this when Philando Castile was murdered right outside of our greenhouses,” Bryant Jones, a plant science major at the University, said. “He was more or less murdered outside of these fields where we do research on, every day.”

Still, Jones participated in “Where It Starts,” which featured his role in cooking for more than 15 hours to feed protesters in Minneapolis following the death of George Floyd. Jones is also the co-founder of Twin Cities Relief Initiative, which provides the food, clothing and other essentials to the community immediately affected by the aftermath of Floyd’s death. Today they assist those in need.

Jones said the University should give credit to White because she “put together a great program,” even though the University is late to the party.

“It’s something we can get behind because it’s something that should’ve been done a long time ago,” Jones said. “This is something that should’ve been done, especially with the diversity talk that the University loves to throw around.”

The question, he suggested, is whether this can move from words to action.

“I believe that the U doesn’t get in the way of diversity and they will support people breaking the ceilings, but the University also has to empower people from marginalized communities because that’s how actual change happens,” he said.

Dr. Terrion Williamson, an associate professor of African American & African Studies with faculty appointments in Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies and American Studies, agreed the series is worthwhile — but only if it translates into investments that empower Black communities.

“I think that there’s power in narrative and I think that there’s power in people being able to tell their stories the way they want to,” Williamson said, although she noted that the project is entirely “individualistic” and requires more to make true change.

“Highlighting those stories for other Black people at the University is important, but what does putting profiles on the website ultimately do?” Williamson said.

If not, she said, it risks becoming just another branding opportunity, which is ultimately harmful.

“It can very easily become a branding exercise, in which the University can highlight their ‘diversity,’ however, if these stories are going to be highlighted, and there’s a greater investment in the very communities that are being highlighted by way of these stories, then I think it’s a worthwhile endeavor,” she said.

Ayuk said she understands how individual stories fall short of perceived activism, but she argues stories can be a form of true activist change — particularly in the past year.

“I’d argue that it is activism because I want people my age especially to retire the idea that activism can only be protesting, organizing, lobbying. That’s simply not true,” Ayuk said in an email. “This is literally the point that I am speaking to in my video… Activism can be Black joy, music, art, dance and storytelling. We literally weren’t allowed to read and write, and now we are writing and sharing our own stories outside of our communities.”

For Ayuk, while more remains to be done, the narratives are a good start to empowering Black voices and acknowledging their experiences.

“Stories like mine and the others in the series restore our faith in humanity, motivate us and make us feel seen, which consequently validates the disappointment, fatigue and isolation we’ve all felt particularly in the past year and encourages the joy we’re allowed to have amidst it all,” she said.