Findings show racial isolation in classrooms affects performance, comfort on campus.

By Eric Servatius

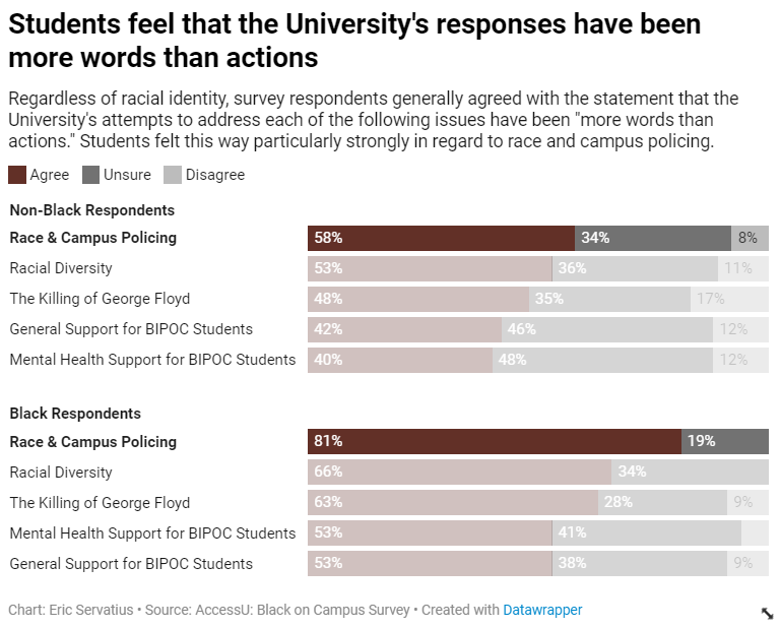

When it comes to addressing systemic racism on campus on a range of matters, particularly with race and policing, a majority of students surveyed — Black students particularly — say the University of Minnesota is simply more words than action.

That is the primary finding of the AccessU: Black on Campus survey administered to UMTC undergraduate students in mid-March.

The survey, circulated in late March, sought to examine the daily realities of students on campus, their relationships with administration and peers, and the ways their racial identities impact these experiences.

In addition to distrust in the University’s stated efforts to address systemic inequalities, the survey identified several other important issues:

- Over half of all survey respondents believe the University cares more about recruiting racially diverse students than it does about supporting those students once they arrive.

- Black respondents were significantly more likely than any other group to say they “always” or “often” feel as if they are the only person of their racial identity in a course. Additionally, over one-third of Black respondents stated that their academic performance was “extremely” or “somewhat” negatively affected by this.

- Black respondents reported feeling pressured to change their behavior in order to be more accepted by their professors at rates higher than any other racial demographic. When asked whether their racial identity was a factor in that pressure, nearly every Black respondent said that it was.

Details of the survey

The survey was disseminated by email between March 20 and 29 to a randomly selected group of 5,000 undergraduate students at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, as well as Black student groups. Of the 342 respondents, 38, (approximately 11%) identified as Black or African American—a response rate notably higher than the just under 7% of the total UMTC student body that Black and African American students make up.

Given the small sample size and collection methods, however, it is important to note that the survey is not statistically significant and cannot be taken to be representative of the student body as a whole. In essence, the survey is a large questionnaire.

As such, it provides insights that are helpful for understanding attitudes and experiences of the respondents, particularly those who are from a marginalized population on campus.

The survey also provided an opportunity for respondents to leave comments and, for some, their name and contact information for follow-up interviews.

More words than actions

The majority of survey respondents, regardless of racial identity, believed that the University’s attempts to address racial inequalities have been more words than actions.

The survey asked this “words/actions” question about University actions regarding the death of George Floyd, campus policing, racial diversity, mental health resources, and support for BIPOC students.

For all students, responses leaned in the direction of “words” for all except the question of mental health resources, where it was split 40% “words” and 48% “actions.” For Black students, however, the split was far clearer, with students noting that “actions” were lacking on all matters despite continued emails reporting policy reviews or following incidents.

“We get a bunch of emails from the U each time a crisis happens, but nothing changes structurally,” wrote one respondent. “We know the crisis occurred, if you’re not going to actually make any type of change, then don’t send an email.”

On average, 48% of all respondents stated that they believed the University’s attempts to address each of these areas had been more words than actions — only 12% disagreed. The results were even more stark for Black respondents, with 63% agreeing and only 8% disagreeing on average.

“Unfortunately, the university has done a poor job about implementing diversity and inclusion for BIPOC [students],” wrote another survey respondent. “They have said more about the issues rather than taking any real actions.”

Even respondents who had more faith in the sincerity of University policies criticized their implementation.

“I feel like there isn’t much information about safety, security and support for POC and marginalized groups,” wrote one respondent. “It’s almost like they have the program, but not enough done to reach out for those who need help.”

Consequences of a lack of diversity

Students who identify as Black or African American make up just under 7% of the total undergraduate student body at the UMTC. Often, Black students are one of the only, or sometimes the only, person of their racial identity in the classroom.

Of the survey respondents who identified as Black, not a single one answered that they “never” felt as if they were the only person of their racial identity in class.

Furthermore, three-quarters said they “always” or “often” feel this way — a percentage which far exceeds that of other racial minorities. As a point of reference, 41% of respondents who identified as Asian said they experienced this in classrooms at the University.

More than one-third of Black respondents said this racial isolation in classrooms has an “extremely” or “somewhat” negative effect on their academic performance.

Beyond academic performance, respondents reported that the lack of diversity on campus also creates pressure to change their behavior — if they don’t, they may not be accepted by professors.

Of the respondents who identified as Black, 50% stated that they felt this pressure from their professors compared to the 33% of non-Black respondents who answered the same way.

Among those who answered that they do feel this pressure from professors, 83% of Black respondents attributed it to their racial identity while only 38% of respondents of all other racial identities felt similarly.

Recruitment vs retention

In February, University administrators outlined to the Board of Regents a plan to increase the number of students and faculty of color at each of its five campuses year over year by 2025.

While the plan also included improvements to the climate students will face once admitted, the survey respondents remain skeptical: More than half of all survey respondents stated that they felt the University cares more about recruiting racially diverse students than it does about supporting those students once they arrive.

It is unclear how much this sentiment has affected Black students’ decisions to stay at the University.

When Black respondents were asked whether they had considered transferring to a different academic institution, one-third stated that they had thought about it — 10 percentage points higher than white respondents.

When those Black students were asked the main reason for wanting to transfer, three-quarters said it was because they disliked the campus environment. By contrast, 37% of non-Black students said the same.

For some, at least, the lack of support for their racial identity has been a factor.

“I came here hoping to enjoy ‘the college experience’ but quickly realized I was the only Black person almost everywhere I went, and it became clear that I wouldn’t be having such a good experience,” wrote one respondent. “Things have not changed and I have never felt comfortable or safe or outright welcome on campus. I feel like I am there just to help the U ‘show’ how diverse they supposedly are.”