Students note some stigma in faculty interactions and expressed concerns about campus police in mental health crisis response

By Mitchell Levesque and Matthew Voigt

Long wait times for appointments, poor help with referrals and challenges accessing information about resources are among the difficulties respondents cited when seeking mental health services at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus, according to a recent AccessU: More than Stress survey.

A majority of the undergraduates who responded to the survey, conducted in March, said they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition in their lifetime — many before they started college. Other notable findings in the survey included:

- an interest in peer specialists who can offer non-clinical support for mental health conditions;

- concern about relying on campus police as responders to mental health crises;

- uncertainty among those who lived in the residence halls about the ability of residence hall staff to deal with mental health crises;

- some stigma around mental health issues on campus, which occurred mostly among peers followed by classrooms and faculty interactions.

Although many of the survey respondents said they were satisfied with campus mental health services — such as individual therapy through Boynton or Student Counseling Services (SCS) — many others expressed difficulties accessing those resources, particularly if the mental health conditions required prompt attention or more than limited treatment.

“The availability of counselors is embarrassingly low,” one respondent said. “I should not have to wait nearly two months for an intake appointment; It’s great you’re advertising these resources but they aren’t accessible.”

Another respondent wrote: “Even when I got my diagnosis, they didn’t follow-up with me. I didn’t have the initiative to go back in the midst of everything else going on, and they forgot about me…It’s not the therapists’ faults (in fact, they’re great), but there’s not enough resources for the scale in which people are struggling these days.”

Methodology

The AccessU: More Than Stress survey, sent to 5,000 individual undergraduate student emails at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities in March, received 512 responses. Questions asked about satisfaction with the University’s mental health services as well as stigma around mental health present in the general campus environment.

Among respondents, 52% said they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition in their lifetimes.

Notably, the rate of lifetime mental health diagnoses in this survey is higher than in others. In a 2017 national study, the American Psychological Association found that 36% of college respondents reported a mental health diagnosis. The discrepancy could suggest students with mental health diagnoses were more likely to take the AccessU: More than Stress survey because its email subject line piqued their interest in mental health.

Due to the sample size and collection method of this survey, it should be considered a large questionnaire; its findings are not statistically significant and cannot be taken to be representative of the student population as a whole.

Comments offer insight

The survey also offers insight into the concerns of students who navigate the campus with mental health diagnoses, which are often not apparent to professors or peers. In 133 comments collected via a free response section, respondents reflected frustrations about the time it took to get a provider and the time between appointments at both Boynton and SCS. Additionally, many respondents raised concerns about the accessibility of disability accommodations in classrooms for mental health conditions and instructors’ respect for those accommodations.

Comments also suggested that respondents see the University as well meaning in its attempt to address student mental health. But some think its efforts miss the mark by primarily focusing on reducing stress instead of services for specific diagnosed conditions, which marginalizes students with more severe mental illness who need those resources.

“I’m sick of feeling like my experiences of mental illness, as someone who has a severe mental illness, are minimized in service of a narrative around how the U is supporting mental health and how we all have mental health issues,” wrote one respondent. “But we’re really just talking about how people can get stressed and have seasonal disorders because we live in Minnesota — not about the whole breadth of mental health and mental illness.”

Another respondent wrote: “It seems there is not much awareness about the variety of mental health concerns that people have and deal with nor is there understanding about the severity. It seems if I mention mental health, again, it is looked at as being mildly anxious, overwhelmed or tired. It’s a little sad that we would dilute the term so much.”

President Joan Gabel has launched a three-year effort to improve the University’s approach to student mental health. The plan, known as the President’s Initiative for Student Mental Health, or PRISMH, launched a year ago with a $100,000 commitment and multiple task force efforts on prevention, research, allyship, services and communication.

Most respondents — 92% — said they had never heard of it.

Services good for many, not for all

Despite some concerns about mental health resources on campus, respondents who sought those services mostly reported satisfaction with their experience — whether that involved looking for those services or using them. More than half of respondents — 58% — who said they had tried to access information about campus mental health resources said their experience was easy or somewhat easy. By contrast, 41% found it difficult or somewhat difficult.

More than half — 59% — of respondents who had used services said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their experience; 40% reported being either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Satisfaction levels were similar between respondents who had used Boynton mental health services or Student Counseling Services for individual therapy.

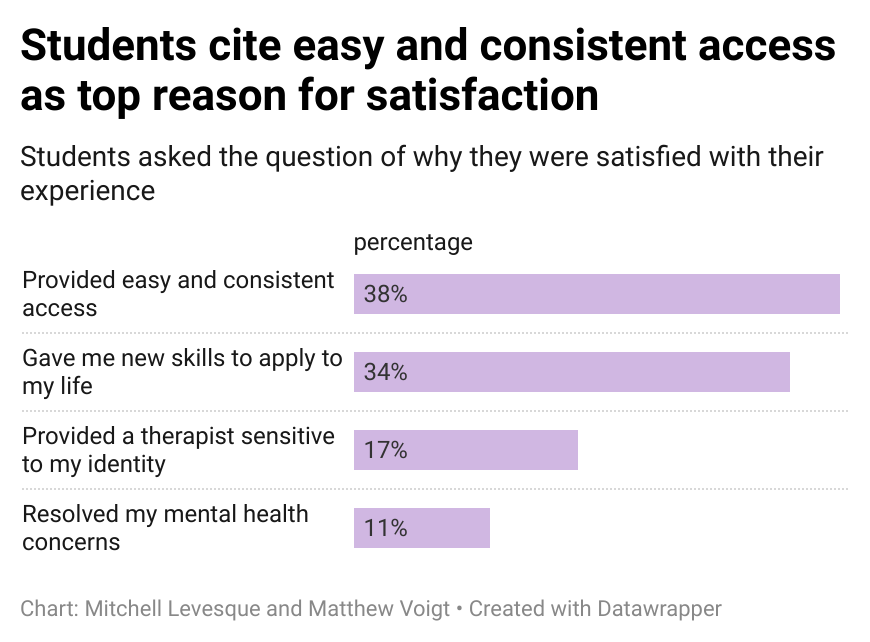

Among the main reasons respondents reported satisfaction were easy and consistent access to the therapy as well as learning new skills that could be applied to their lives. A notable 17% said they were provided with a therapist sensitive to their identity.

Of the 72 respondents who specified why they were dissatisfied with the University’s mental health services, more than one-third said it was because they were told they could not receive care at that campus resource and were given either no help or poor help with a referral for services elsewhere.

On average, about 15% of the roughly 600 to 650 students per week who are seen in Boynton’s mental health clinic are eventually referred elsewhere, according to Matthew Hanson, the interim director of Boynton’s mental health clinic. This is either because the clinic’s 10-visit limit per year isn’t enough to address the student’s condition, or because those with complicated diagnoses require specialized therapies.

Boynton employs two licensed clinical care coordinators whose job is to assist students throughout the referral process and offer them community treatment options during their initial consultation, Hanson said in an email to AccessU: More than Stress.

“We know that navigating community mental health systems can be a challenge, and our staff members routinely help students with this process since many are accessing care for the first time on their own,” Hanson said in the email. “It’s unclear if the survey respondents had direct contact with a professional provider who could assist with making a referral to the community.”

In the survey comments, several respondents said the referral process didn’t always help them.

“I was turned away from counseling because I was ‘too severe a case’ and it would be ‘unfair to us both’ to try to do biweekly counseling,” wrote one respondent. “I was given a packet of phone numbers and that’s it.”

Another respondent wrote: “I had a friend who was denied services because she was ‘too mentally ill,’ but was unable to get services elsewhere because she does not have health insurance. I think the University’s services would have been better than nothing, and turning her away was absurd.”

Peer support and groups might help

The majority of students indicated they would be interested in additional mental health resources — beyond individual therapy — to support their mental health. The strongest interest was in peer specialists, people with a mental health condition who are trained to offer structured support to others with that condition. Compared to other possibilities, such as group therapy, peer support groups or a mental health living learning community, peer specialists were selected as an option more than all those other choices combined.

Several of the comments suggested the campus needed more support for mental health beyond individualized therapy, such as “low-stress” peer support groups or individualized peer counseling.

Since 2015, Boynton has offered peer support through its de-stress program, which provides one-on-one meetings to assist students with managing stress, said Boynton’s Hanson in his email response.

Hanson said the de-stress program was started because research showed peer support can make a difference for students with proper training and supervision. Currently, he said, the demand for de-stress appointments is low and student response to it has been mixed. “The primary concern with peer support programs concerns the qualifications of the students in the supporting role, and the availability of supervision for concerns that require more immediate attention,” Hanson said.

Other comments in the survey echoed concern about alternative support, including the lack of “services near campus like NAMI [National Alliance for Mental Illness] support groups that are more accessible, inclusive, and experienced with support,” or regular groups that target specific issues such as eating disorders.

Boynton does not treat students who “present with active eating disorder concerns” but instead refers those students to nearby specialty clinics, according to its website. Survey respondents said in comments that eating disorder referrals from Boynton worked well. One comment noted a need for additional on-campus support once treatment ended.

“As someone who is in recovery from anorexia, I have had a hard time with my transition to college. I wish that there was some kind of campus support group or advocacy for students recovering from eating disorders,” wrote one respondent.

Confidence in a crisis low for police

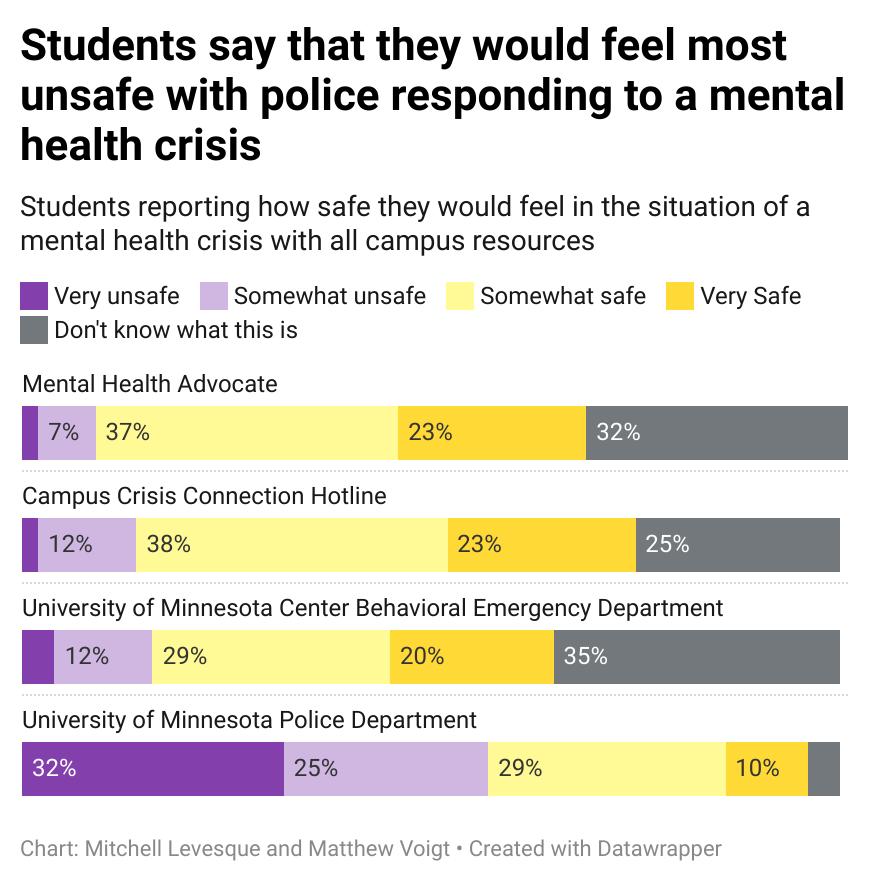

About one third of respondents — 115 in all — said they had used one of four campus services for a mental health crisis. Those four services were: Mental Health Advocates, which are faculty and staff trained to offer support and resources for students; Boynton’s Crisis Connection Hotline; the University of Minnesota Medical Center’s Behavior Emergency Department; and the University of Minnesota Police Department.

Roughly twice as many respondents reported using Mental Health Advocates and the Crisis Connection Hotline compared to campus police.

A separate question asked respondents to rate how safe they would feel using those services for a future mental health crisis. Mental Health Advocates and the Crisis Connection Hotline received more ratings of safe or very safe, although nearly equal numbers of respondents responded they did not know what these services were.

By contrast, while more respondents reported familiarity with campus police, far more said they would regard the police as unsafe or very unsafe in a mental health crisis.

According to the University’s Safe Campus website, students are directed to call 911 immediately if they or someone they know is in danger of a mental health crisis.

While most survey respondents did not live in campus housing, of those who did, the majority — 60% — said they felt somewhat uncertain or very uncertain about whether Housing and Residential Life staff could effectively respond to a serious mental health situation.

In an email to AccessU: More than Stress, Jessica Gunzberger, coordinator of residential life, said that community advisers (CAs) are trained to support residents with the general stress of college life as well as mental health crises.

“CAs are trained to identify when a situation is outside the scope of their role as student staff,” Gunzberger said in an email. “In those situations, CAs are trained to contact the [Campus] Crisis Line and have residents speak to them. Anytime a CA is concerned that a resident is an imminent threat to themselves, the CA will contact the police.”

Stigma tied to peers and faculty interactions

For those who said they had a mental health diagnosis, about half said they had experienced some form of mental health stigma, which the National Alliance on Mental Illness defines as: “when someone, or even you yourself, views a person in a negative way just because they have a mental health condition.” More than two-thirds of respondents who had those encounters said they were infrequent or very infrequent. But when encounters occurred, they most often happened among peers. Classroom settings and faculty interactions were also places where stigma occurred.

When instances of stigma happened with faculty members, top reasons cited were instructors’ insensitive responses to a student’s mental health situation, followed by the instructors’ handling of accommodations from the Disability Resource Center. Some respondents cited instructors’ lack of inclusivity or cultural awareness as the source of stigma.

Comments in the survey suggested faculty response to struggling students is, at best, an uneven one — and it is one area that can make a big difference:

“When it comes to faculty I’ve had one professor act as an advocate and communicate their concerns towards students’ mental health, but other faculty seem to be dismissive of how mental health can affect performance on course work,” wrote one respondent.

Another wrote: “I had to leave school to go into inpatient [care] for my eating disorder last year. The DRC was extremely helpful through this process and most professors were understanding, but I have experienced some insensitivity from professors upon leaving and since my return.”

Several comments suggested a more compassionate faculty approach would benefit everyone.

“Mental health resources are useless if you don’t have the time to use them,” said a respondent. “Professors need to create spaces and syllabi where students can ask for accommodations regardless of ‘official’ diagnosis or emergency… and be willing to help their students with accommodations regarding deadlines and attendance before said students are on the metaphorical ledge ready to jump.”