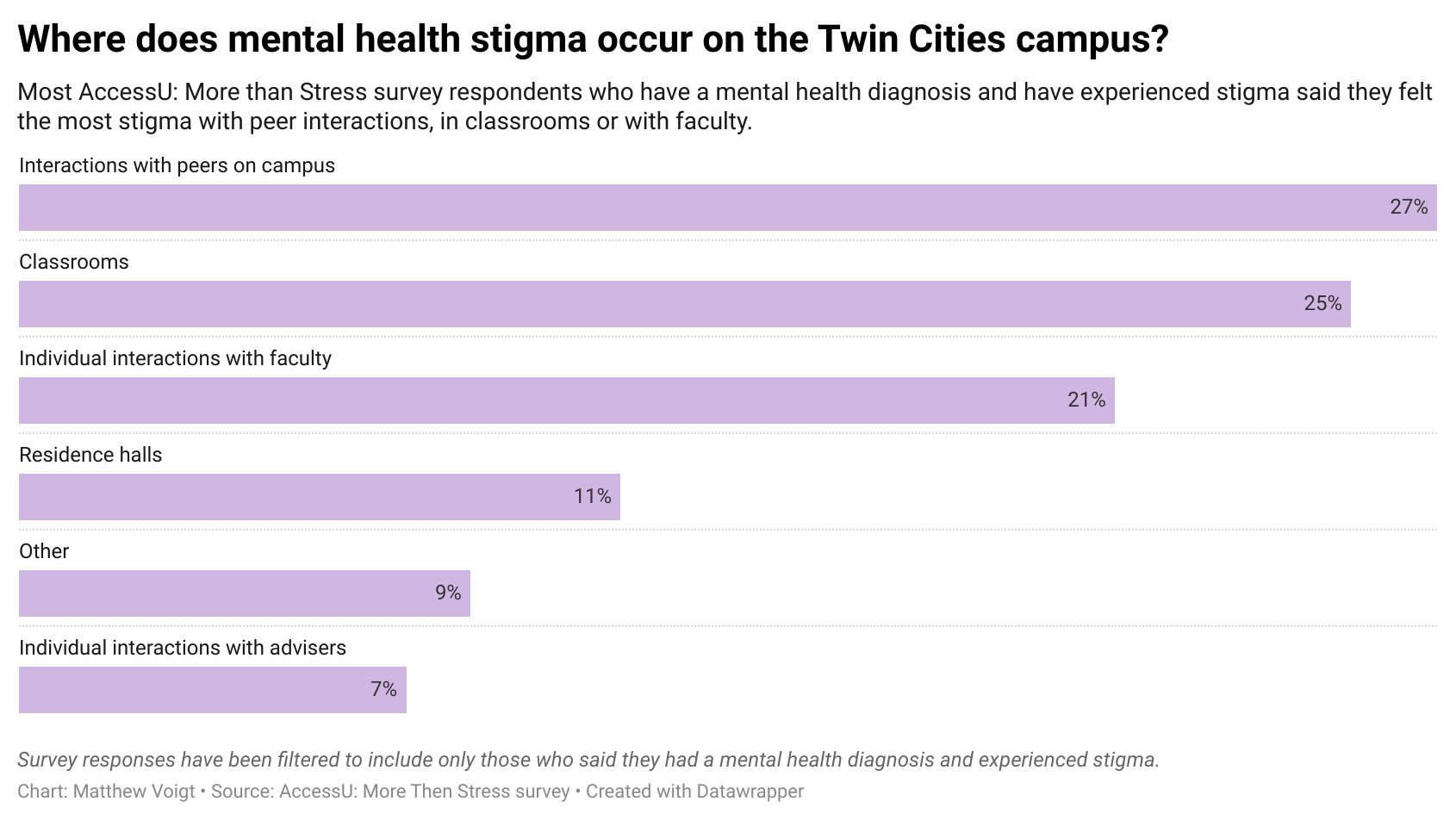

Graphic: People who reported having a mental health diagnosis said that when they felt stigmatized, they felt it most often during interactions with their peers followed closely by in classrooms. However, a notable percentage had experienced stigma in faculty interactions.

A recent AccessU: More Than Stress survey evaluated mental health on campus, including student and faculty experiences with mental health based stigma

By Emily Baude, Eitan Grad, Anna Koenning and Mikayla Scrignoli

When University of Minnesota nursing student Spencer Schmid, who is diagnosed with anxiety, presented a disability accommodations letter in a class during sophomore year, the professor asked for the diagnosis behind it.

By law, such letters do not list diagnoses. Instructors are not supposed to make such requests.

But the professor explained she needed to make sure Schmid would not be a “danger to patients,” Schmid said.

“You hear about stigma and you understand it exists, but to actually be confronted with that in the moment was so shocking to me,” Schmid said. “I really didn’t know what to do because this was a professor… there is a power imbalance, like they have a lot of control over your academic success.”

According to an AccessU: More Than Stress survey, students experience stigma relating to their mental health diagnoses infrequently on campus, but when they do, they can occur during faculty interactions such as the one Schmid described. This could include discussions related to disability accommodations, absences related to mental health or other course requests related to unanticipated mental health situations.

Sensitivity around student mental health issues has become unavoidable for faculty within the past decade. According to Boynton’s student health surveys, 51.7% of students at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities have been diagnosed with a mental health condition at some point in their life compared to 27.1% in 2010.

Some instructors say that awareness of mental health stigma is increasing along with accommodations for students who need them, including official accommodations from the Disability Resource Center (DRC). More than 50% of accommodations handled by the DRC involve mental health conditions, according to the center’s staff.

Within the past five years, the University has developed initiatives to increase awareness among faculty about student mental health, including a recent effort to create mandatory training on accessible course design and best practices for working with students on accommodations. Some instructors are part of a voluntary program called Mental Health Advocates (MHA), which trains faculty and staff in best practices for accessing mental health resources and for promoting “a University culture that is welcoming and accessible to students,” said Kate Elwell, senior health promotion specialist at Boynton who organizes the program.

Such actions reach only a part of the faculty. There are 364 Mental Health Advocates, for instance, and some of those are advisers and other staff. The University had 4,696 full- and part-time instructors during the spring semester of 2022.

And despite the progress, students say stigma related to mental health from faculty happens unwittingly and in subtle ways, often stemming from instructors’ skepticism that mental health conditions such as anxiety or depression are not as serious or not as real as physical illnesses.

As a result, typical and even well-meaning faculty responses about classroom policies, or about drive and motivation, might be experienced very differently by someone who lives with chronic mental illness, said Ben Munson, professor and chair of the speech-hearing-language sciences and a member of the Disabilities Issues Committee.

In other words, Munson said, a message of “you’ve got to pull yourself up by your bootstraps” can be experienced as: “I don’t feel safe.”

Stigma infrequent but present

The National Alliance for Mental Health defines mental health stigma as “when someone, or even yourself, views a person in a negative way just because they have a mental health condition.”

A 2017 joint Faculty Consultative Committee (FCC) and Provost Committee report on student mental health listed examples of stigma in the classroom including using words like “nuts” and “wacko,” joking about mental illness or using stereotypes of mental health conditions.

The report recommends that professors educate themselves on mental illness and successful people with mental illness in their fields, to understand the common symptoms of mental illness and to be vulnerable about their own experience so that students feel comfortable approaching them.

Stigmatizing experiences on the Twin Cities campus do not appear to be frequent, according to the AccessU: More Than Stress survey conducted in March. While about half of respondents with mental health diagnoses said that they felt stigma based on their mental health condition on campus, nearly 70% said that their experiences with stigma were very infrequent or infrequent.

A good many of those experiences are also with peers, not faculty, the respondents said. Over a quarter of respondents with mental health diagnoses indicated that they experienced stigma in connection with peers.

Hafsa Mire, a fifth-year mass communication major and psychology minor who has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, anxiety and severe depression, said that she felt judged by her peers and friends on campus when she missed in-person classes due to her mental health.

“I know one of my friends, she couldn’t understand it,” Mire said. “Because I would have panic attacks from the walk from the building. I was already in the classroom and it would get so bad that I would just turn back and then not go to class that day. And it was difficult for her to understand why I was having such a physical reaction to just attending class.”

Donald Bystrom, a second-year industrial system and engineering student with bipolar II and depression, said he is also reluctant at times to talk about mental health and symptoms to friends and peers on campus.

“I choose very carefully how much I want to divulge to who, depending on how close they are to me or what situation I’m in,” Bystrom said. “But even friends and acquaintances or classmates, sometimes I can’t necessarily hide how I’m feeling or what’s going on that day. But I still try to reduce how they see me because I can tell that there is some stigma just in general, in some classes, or with some particular, you know, other students.”

Stigma and insensitivity

Additionally, a quarter of survey respondents with mental health diagnoses said they experienced stigma in the classroom or during interactions with faculty – in other words, with those who are commissioned to teach and guide students during their college years. Insensitivity to personal circumstances and a lack of awareness of cultural differences were the main reasons experiences with faculty were stigmatizing, according to the survey.

Third-year neuroscience major Roberta Rooker said that stigma comes through when professors do not respond to the proactive ways she tries to manage her diagnoses of ADHD, anxiety, depression and PTSD through emails or even her initial communication about disability accommodations.

“So they either tend to not respond to emails, they don’t respond to the initial DRC accommodations, or they’re just not really accommodating at all,” she said. “It feels very much like, ‘Oh, you can’t do your homework, but everybody else can? That sounds like an issue for you and not me.’”

The DRC is set up to help students manage classes with their disability by giving them tools, such as deadline extensions, extra time on tests or flexible attendance, so they can work with instructors to create reasonable accommodations for the course.

Sohail Akhavein, a manager for student access at the DRC, said that policies and procedures in the classroom are paramount to making a course accessible. For years, the Center for Educational Innovation has encouraged faculty to incorporate universal design for learning tools that permit students to access a course in a variety of ways, not just through classic lecture and note-taking. Such strategies can make the course more accessible to students who need to miss class.

“If a faculty member were to incorporate inclusive design strategies within their courses, that removes some of the attitudinal potential barriers that students experience,” Akhavein said.

Students just don’t disclose

Concerns about stigmatizing reactions can be especially acute when students face mental health setbacks not covered by a disability accommodation, according to interviews conducted with survey respondents.

Some students were so wary about professors’ responses to such situations that they weren’t comfortable disclosing a mental health reason for an absence, even though it would be covered as a legitimate circumstance for missing class, according to University policy. Under that policy, the student would be allowed to make up work missed from the absence, assuming the student complied with other aspects of the policy.

Ava Thompson, a fourth-year political science major with depression, said that she told one professor that she had a physical health condition when she missed class due to her mental illness.

“I went through a phase during my sophomore year where I was really not feeling great at all, and instead of telling my professor that I have this mental health condition, I instead said I have a really bad cold,” Thompson said.

Biosystems and bioproducts engineering student Lauren Stach said she didn’t feel comfortable telling professors about her inpatient treatment for an eating disorder that caused her to take a leave of absence last fall.

“I just said it was a health issue because I wasn’t sure how it would have been received,” she said.

Mire said she has also felt stigmatized by interactions with some professors. This spring, with just one semester needed to graduate, she enrolled in an in-person course after a long period of only remote instruction. She sent the professor her accommodation letter and tried to attend class. On the first day, she said, coming to campus proved too difficult for her. She emailed the professor to explain her situation and asked if she could attend the course remotely or find a way to earn points even if she could not attend classes every day.

According to the email exchange with the professor, which she shared with AccessU, the professor said it would not be ethical for him to approve that request and that she could not meet the learning objectives with such spotty attendance. He suggested she enroll in an alternative class offered remotely. Mire appealed, writing back to ask, among other things, if she would “absolutely have to attend every class to earn the points.” The professor again denied her request, this time with an email that began: “Well, since you clearly have not read the syllabus for the course, where it states there are no points for attendance, I’m somewhat skeptical of your commitment to this process.”

The professor acknowledged further down in that email that he was sorry she was struggling and that he was “not unsympathetic to her requests.” But Mire said what bothered her about that interaction was not the denial but rather what she described as the professor’s arrogant manner at the outset of the email, which overshadowed his later statements.

“I remember thinking, this person has no clue what’s happening in my life. And yet, he thinks because he has some sort of dignity, he has a right to sit there and judge me,” Mire said. “I understand, even if you feel that way, but there’s a certain way to talk to people.”

Perceptions over realities

Some survey respondents called out specific colleges at the University for being particularly prone to stigmatizing or insensitive behavior. One respondent wrote: “ [College of Biological Sciences] practically pretends mental health doesn’t exist and is pseudoscience. ”

Professor Robin Wright, who works in the College of Biological Sciences said that this comment does not reflect her perspective or that of her colleagues in the dean’s office or the departments within that college.

“That statement is very disturbing to me,” she said. “I hope it only represents a conclusion based on an experience with an individual class or professor, and not multiple situations.”

Wright said that making her classroom a safe environment to discuss student mental health starts in the syllabus, and while she doesn’t ask about students’ health or why they missed class, she said that many voluntarily share.

“I certainly sense that the students are very open, probably more so than I like to be with my colleagues,” she said. “I am ultra-careful to make sure I don’t abuse that trust.”

Wright said that many instructors’ view of stress and mental health in the classroom has changed over the past decade as more students with diagnoses have more openly discussed these in classroom settings. Now, she said, there is a “growing awareness” among instructors on the role of mental health in the classroom.

“I think like a lot of things, it wasn’t our job,” she said of student mental health. “It’s like we said our job wasn’t to teach students how to think, it wasn’t our job to teach students how to write, and then of course it is our job to teach students how to think and write even though it’s a biology class.”

Equity-minded teaching

Chemistry professor Phil Buhlmann has long held the view that it is important to understand and talk about mental health in his department and in others.

“What I’ve been trying to push in our department is kind of that philosophy that we as a department or as a program, we consider attention to stress and mental health a professional duty of us in our profession,” he said. “I think that’s one of the biggest roles of faculty is that we talk about this openly.”

In his experience giving talks on student mental health to other departments, Buhlmann said that professors are interested in learning how to create a classroom that accommodates stress and mental health conditions.

Making that leap means changing the idea of “equal” treatment in the classroom to that of equitable treatment.

Wright said that instructors treat students equally instead of offering accommodations for students who need them.

“I think that many of our colleagues are far away from understanding what equity means,” she said. “A lot of professors think that they have to treat everybody exactly, exactly, exactly the same,” she said.

Instead of treating students equally, Wright accommodates those who need it.

“The way we teach, and I’ve been doing this for many years, is to give as many accommodations as we can until the time runs out and the semester is over,” she said.

The 2017 FCC-Provost Committee report recommended that instructors build flexibility into their courses, offer extensions to students with mental health conditions and to focus exams on what students know rather than how quickly they can work.

“Instructors need to acknowledge that an accommodation request for any disability, whether physical or mental, represents an actual problem; it does not mean that a student is trying to hide behind excuses,” the report said. “Nor does providing accommodation constitute hand-holding.”

The report also suggested that professors “use and share resources for promoting positive mental health” and that they model healthy coping skills.

Training and compassion

New efforts are underway by the University to help faculty improve responses to student mental health needs.

The three-year President’s Initiative on Student Mental Health, also known as PRISMH, has no specific focus on stigma, per se, but one of its work groups will focus on allyship and early detection to work with faculty to adopt “a mental health-centered approach” to syllabi and other class activities.

Currently, Munson and a team of faculty and students are working on a training module which, if implemented, will be required for teachers on how to make classrooms accessible for students with disabilities, including mental health conditions.

The training will include three 15- to 20-minute modules on rules about disability accessibility, the basics of disability accommodations and universal design for learning. To make his classroom accessible, Munson offers a synchronous Zoom class in addition to his in-person one, posting recorded lectures online and allowing ample time for online exams.

Instructor input has been a significant piece in the process of creating the faculty training modules, Munson said. Indeed, some faculty worried that providing accessibility could diminish their freedom in the classroom, but Munson said that in the end, instructor reactions to the training have been “overwhelmingly positive.”

As for asking students to confront faculty when stigmatizing behavior occurs, Akhavein from the DRC acknowledged that may be too much to ask. “Many students might feel uncomfortable disclosing that they are navigating difficulty because of the natural power dynamics that occur” between students and instructors, Akhavein said.

Mire said she believes compassion and empathy would help decrease stigma. Students who are approaching professors about their mental health are likely already struggling, and so a compassionate response can make a real difference, Mire said.

“Culture plays a role in how we perceive mental health. And I think that’s why it’s so important for places like the [University] to consider people’s backgrounds and experiences when it comes to dealing with accommodations and their mental health,” Mire said. “I just think anything and everything can affect your mental health. It’s very important to make sure that your experiences are validated.”