Survey: UMTC nontraditional students work longer, prefer online classes

Results show students who come to campus on varied paths have mixed feelings about their experience: “I feel empowered, and also intimidated, and like I don’t belong.”

By Dylan Anderson and Charles Ouellette

The majority of students who enroll as freshman at the Twin Cities campus each year come straight out of high school on a “traditional” four-year degree path.

But plenty of other students come to the University later on a nontraditional path — delaying enrollment, taking courses part time or sidelining school with work or family obligations.

What do we really know about the university experience of such nontraditional students?

A survey, disseminated by AccessU: Nontraditional Paths in mid-March just as the university was closing down its in-person classes, gives us a glimpse of some key issues:

- A larger share of nontraditional students work jobs outside of classes, and they work those jobs for longer hours than most students. The work they do causes them to miss class more often than traditional students, and sometimes, they say, it gets in the way of pursuing career-enhancing opportunities such as internships.

- The basics of scheduling and classroom dynamics can sometimes be challenging. More nontraditional students struggle to find classes that fit their needs than traditional students, particularly in the evening or during summer session. In the classroom, faculty are usually supportive. But those who cite classroom challenges say group work and getting along with peers are the main difficulties.

- As a group, nontraditional students are slightly more open to online instruction, although not overwhelmingly so. As the campus prepared to shift to online instruction because of the COVID-19 campus shutdown, nontraditional students reflected less worry about that change than traditional students. Separately, when those students were asked to name the No. 1 resource the University could provide to better serve the needs of nontraditional students, the top choice was more online courses.

- For nontraditional students who struggle with mental health, three-fourths said it was a factor in their decision to take a nontraditional college path. The survey also found that 65 percent of traditional students who struggle with mental health say they have considered actions such as taking a leave or going to school part-time, which would send them into a nontraditional path.

And in many of more than 90 comments left on the survey, nontraditional students reflected both pride about what they are achieving yet alienation from their campus peers. The comments also suggested the University’s focus on minimum credits and four-year degree completion creates a narrative that overshadows the diverse needs of nontraditional students, especially in orientation programs and advising.

“I feel empowered, and also intimidated, and like I don’t belong.”

“Nontraditional students are very focused and driven because we have a lot to lose but so much more to gain if we achieve our goals.”

“I think there should be more campus-wide information about nontraditional paths in higher education. One can feel that taking a slower path is incorrect when the traditional way is so frequently pushed to students as being the superior way.”

“This is the first time I think I’ve had acknowledgment that I am a nontraditional student. Though I am around the age of my peers, our vastly different experiences and not living on campus make it really difficult to feel like I fit in.”

The survey details

The survey was disseminated by email between March 14 and 22 to 5,000 degree-seeking undergraduates as well as 700 non-degree-seeking undergraduates on the Twin Cities campus. More than 900 people responded, with roughly one-third indicating they were nontraditional students according to the University’s definition of that population.

The University currently defines nontraditional students as those who have delayed their enrollment, are enrolled part time, work full time, are parents, or do not have a high school diploma.

The survey results do not reflect statistical representation of the larger Twin Cities student population. Although it was sent out to a randomly generated set of emails, it’s likely many of those who took the survey were drawn by the email’s subject line and message about nontraditional student issues. As a result, the sample may reflect a larger-than-usual population of those students.

However, the information is useful as a large questionnaire to measure the attitudes and experiences of those students.

At the end of the survey, students were asked to leave comments and to give their contact information for follow-up interviews. Ninety-seven nontraditional students left comments, and 94 gave contact information.

An inadequate definition?

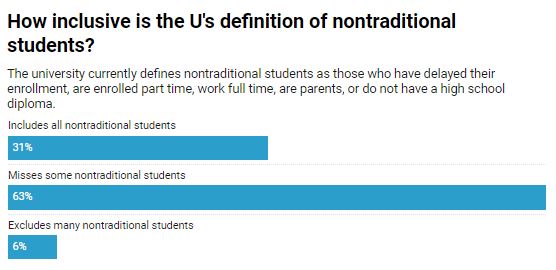

A majority of survey respondents , regardless of their path through college, agreed that the University’s definition of a nontraditional student falls short.

Fewer than one-third of all the survey takers said they were satisfied with the definition as is — again, restricted to students who delay their enrollment, are enrolled part time, work full time, are parents, or do not have a high school diploma. Almost two thirds said that it was an OK definition but misses some students who experience a nontraditional path at the University.

“Most people don’t take a so-called traditional path,” wrote one student. “It is to me kind of old-age thinking to think of it as traditional and nontraditional.”

Some of the comments sought to expand the definition to include students facing health issues or disabilities, including mental health issues, as well as international status, those returning to school on a different career path and senior citizens who take classes. More expansive definitions of nontraditional can also include students who are veterans, low-income or first-generation.

To one commenter on the survey, the definition should be even broader.

“Nontraditional in my mind is any student who is not coming to the University as a freshman coming directly out of high school,” that student wrote.

Working often, longer

Most survey takers, whether traditional students or not, said they worked a job while attending the University. For students identified as traditional, 60 percent said they work a job outside of being a student. For nontraditional students, that portion was 82 percent.

The number of hours differed significantly between the two groups.

Most traditional students who worked — 80 percent — said they work less than 20 hours a week.

By contrast, many nontraditional students are working long hours. About 70 percent of working nontraditional students said they worked 20 hours or more each week. Almost half of them said they worked more than 30 hours, with 15 percent saying their work exceeds 40 hours a week.

Work often got in the way of nontraditional students’ career aspirations and their class attendance. The majority of nontraditional students said they have to miss at least some class because of their work obligations. For traditional students that number was about 30 percent.

“Having to balance a work schedule, class schedule and the rest of what goes into being a graduating senior is like putting together three jigsaw puzzles on top of each other at the same time,” one student commented. “It rarely works.”

More than one third of nontraditional students surveyed also said their work prevents them from gaining relevant work experience for their degree.

“Balancing needing money from my jobs, needing experiences for my career and still needing to study, it becomes overwhelming,” one student commented.

The struggle for classes that fit?

Nontraditional students do not see themselves as disadvantaged academically, although socially it can be challenging for some, they say. Around 60 percent said being a nontraditional student was at least a moderate drawback to their social lives. A quarter of nontraditional students said it didn’t have an effect.

As far as school work, more than half of nontraditional students said their status was either a benefit or had no effect.

Even so, they say it’s challenging to fit school with their lives.

They struggle with finding classes that work with their schedule, especially as they progress to the advanced classes in their major programs. A key frustration is the University’s failure to accommodate them through evening or summer classes. About 20 percent of nontraditional students said the University rarely accommodates their need for these courses.

When asked what the No. 1 resource the University could provide to better serve the needs of nontraditional students, 30 percent chose more online courses, although nearly as many responded they did not know. Additional night courses and improved advising received about 15 percent each.

In the classroom, nontraditional students say faculty are generally supportive. Almost half said that faculty have always been sensitive to their needs, and another third said that faculty were usually sensitive to these needs but cannot always meet them. A small majority — 55 percent — said they don’t face added challenges in classes as a nontraditional student.

For those who did say classes can be challenging, group work and interacting with peers are the main difficulties — far exceeding any concerns about technology or participation in class discussions.

Some comments indicated faculty could be more sensitive to nontraditional students. “We are often harder working than traditional students because we were late to the game or because we are working full-time on top of courses,” wrote one student. “Instructors need to be more sensitive to the needs of non-trad students and better understand their situations. They often ignore us and focus more on traditional students.”

Despite challenges, many comments indicate nontraditional students believe they add value to the classroom.

“Nontraditional students bring such a depth to in-class discussions that is really important,” one comment read.

Switch to online classes was a worry

Uncertainty about moving classes to alternative formats was shared by many students in mid-March, regardless of whether they were traditional or not. Just over 60 percent of all respondents predicted the shift would have some negative impact on their ability to manage their work and school schedules.

Traditional students expressed more concerns about the transition. Online classes were seen as a benefit by around 22 percent of nontraditional students, but fewer than 15 percent of their traditional counterparts.

A quarter of nontraditional student responses said it would have no effect compared to 18 percent of the traditional student responses.

For this question, students were allowed to select multiple concerns. Lack of communication from the instructor topped the worries for both nontraditional and traditional students. About 45 percent of nontraditional students and 64 percent of traditional students said this was a worry.

Both groups were also concerned about reduced access to instructors and their instructor’s lack of experience with the technology to make online classes a reality.

Students also worried about training and assistance the University would offer to students after the shift. A smaller group of students flagged concern about their own technological capabilities, with a higher share of those being traditional students.

Still, nontraditional students seemed to be more at ease with the shift, with about a quarter of them expressing no concerns versus 13 percent for traditional students.

Mental Health

More than half — 55 percent — of all the students who responded to the survey said they struggle with their mental health.

But for the nontraditional students who say they struggle with mental health, three-quarters said it related to their status as a nontraditional student, either by contributing to or being an effect of their circumstances.

Some comments reveal that nontraditional students arrived on that path by taking time off after high school or leaving a previous institution to manage their mental health.

Traditional students who indicated they struggled with their mental health suggested, through their answers, that mental health can play a role in moving someone off a traditional college path.

When those traditional students were asked if they ever contemplated taking any of three actions — quitting school, taking a leave of absence or going to school part time for multiple semesters — more than half said they had considered one of these options. Of these students, more than a third had considered taking a leave of absence.

Many comments from nontraditional students indicated they manage their mental health by taking time off from school or scheduling their classes part time.

“Anxiety and depression interfere with [my] ability to handle a large course load, so I have been trying my best to take a few classes at a time to manage to stay on top of everything,” one commentor wrote.

While for some these strategies are effective to manage mental health, it often forces students to detour from the traditional four-year-path. That, in turn, can create difficulties once the student returns to school surrounded by younger peers.

Many of the comments reflected added pressure of being an older student who takes longer to earn their degree.

“I have a lot of anxiety about being able to graduate by a certain age and whether I am too late to succeed,” one comment read.